The Early Bird Gets the Worm

When MOON OVER MANIFEST won the Newbery Medal a couple of years back it took us by surprise. The book had three starred reviews, but it was a debut novel published in October. It definitely flew under our radar. I enjoyed the book very much and looked forward to Vanderpool’s sophomore effort to see whether or not she would be a flash in the pan.

When MOON OVER MANIFEST won the Newbery Medal a couple of years back it took us by surprise. The book had three starred reviews, but it was a debut novel published in October. It definitely flew under our radar. I enjoyed the book very much and looked forward to Vanderpool’s sophomore effort to see whether or not she would be a flash in the pan.

I’m happy to report that I also like this new one and find it a very strong contender with strengths virtually across the board: plot, character, setting, theme, and style. But, as with P.S. BE ELEVEN, I hesitate to commit one of my first three October nominations to it just yet. Part of that is that I don’t see enough separation in my mind between that top group of contenders to preference a couple of them over the others. And another part of that may have to do with some of my quibbles.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Sondy raised the Pi problem at the end of last season, and I’m going to let her summarize and expand on that again below in the comments. I will say that it didn’t bother me (just as my problems with THE CENTER OF EVERYTHING won’t bother others). I also found the Pi stories really, really cheesy–but I was so caught up in Vanderpool’s storytelling that I hardly cared. What was more problematic for me is that the ending, as satisfying as it is, depends on an awful lot of coincidences, and I think on a second reading when I’m not as enthralled with the storytelling that they will stand out more.

NAVIGATING EARLY sits atop the goodreads poll which often favors books that are published in the spring season, especially in January and February. (Indeed, you have to get past the top ten before you find a fall book.) THE ONE AND ONLY IVAN was also a January book. Does the early bird get the worm? What say you?

Filed under: Uncategorized

About Jonathan Hunt

Jonathan Hunt is the Coordinator of Library Media Services at the San Diego County Office of Education. He served on the 2006 Newbery committee, and has also judged the Caldecott Medal, the Printz Award, the Boston Globe-Horn Book Awards, and the Los Angeles Times Book Prize. You can reach him at hunt_yellow@yahoo.com

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

2024 Books from Pura Belpré Winners

Passover Postings! Chris Baron, Joshua S. Levy, and Naomi Milliner Discuss On All Other Nights

Winnie-The-Pooh | Review

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

Crafting the Audacity, One Work at a Time, a guest post by author Brittany N. Williams

ADVERTISEMENT

I agree with Sondy about the problems with pi. It bugged me, and it was used to try to create tension in the Pi Stories (which I had to force myself not to skim over – though a ten year old I know thought they were the best part, so clearly opinions vary.) Maybe its because I’m an adult and know that pi is irrational, but since I knew solidly that the number 1 would return, it fizzled for me. I’d much rather have the tension arise from “how will this be okay” than “will it be okay” anyway.

The string of coincidences was too much for me as well. I suppose it was supposed to feel like the hand of fate (or the hand of Pi?) guiding the boys to meet a series of people who have a remarkable similarity to the characters in Early’s story, and if it had stopped there, I would have gone along for the ride. But the further connections where it turned out that everyone knew everyone else and they all happened to be in more or less the same place at the same time? That was too much for me.

I did not think it made any sense for the pirate to be following the boys for days through the woods on the off chance that they knew something he didn’t, when he had been living in that area for his entire life. I also found it hard to believe that the lumberjack was watching the escapades for days and did not move to intervene earlier. Yes, he had ptsd and was not in a good place, but the boys were in real and present danger several times.

Also, the first half of the book is filled with too many instances of the phrase”that strangest of boys”.

Clearly I wouldn’t use one of my nominations on it. :-} The setting is well done, I’ll give it that.

ditto :-). Not one of my top choices, either–and for the same reasons! And it’s just plain too long… c’mon, editors. EDIT.

I found the plot overwrought and overdone. Much like Okay For Now, it was a well-written book and distinguished in many ways. I felt like she might as well throw everything in with the kitchen sink plot-wise: dead mom, lost dad, new school, disabled friend, high adventure, killer bear, unsolved missing person case, running from murderous bandits, reuniting long lost love, MIA brother reunited, cheesy Pi parallel, etc.

I get that this book works for many people. I happen to not be one of them.

While I, too, found much of the language overwrought and the coincidences hard to swallow, I think that Vanderpool did an amazing job of setting this all in a context that makes everything acceptable to a *child* reader.

I never totally latched on to Moon Over Manifest though I found its defender’s arguments convincing. I just had a hard time getting into that story. So it was with some trepidation that I opened a book of the same length and disturbingly similar cover (what’s up with that?)…only to find myself absolutely and immediately engaged by Jack. I slapped a post-it on the page whenever there was a passage that was “too much” or “too farfetched,” and I’ve got a lot of them…but somehow the plot and pacing were still utterly compeling.

Yes, the coincidences are numerous. Yet each one is technically, theoretically, plausible; and Vanderpool has convincingly set a tone that forces the reader to learn to see through a different perspective (Jack through Early’s), a perspective in which that which appears random actually has some internal structure. This tone or theme is the net that allows Vanderpool to stretch believeability with her coincidences. And, most importantly, it’s a perspective that is very appealing to children, stimulating, and respectful of them.

I’ve still got lots of quibbles, but each one is minor, and at this point don’t sink the book for me; it’s on my very small shelf of “keep it in mind” titles, along with P.S. BE ELEVEN.

I read this over a year ago so can’t be specific, but did like it a great deal. I was especially delighted with the Odyssey references. That whole section of the book felt so magical to me that I’d defend all the improbabilities (e.g. the pirate following them and so forth). Have to agree with others that the Pi story was a lot less compelling than other parts of the book.

Interesting that several of this year’s potential contenders are historical fiction with what some feel are fatal flaws while others would deem them quibbles. Pi versus Jackson Concert year versus….well, guess Hokey Pokey is something else:)

I think it’s both important and unimportant to really emphasize how serious the pi problem is. It would be like writing, in an otherwise realistic novel, that a baseball game was 4 innings. (Maybe in a novel set in 1845, but in 1945, that’s a head-slapper.) Or it would be like having a professor character make a serious claim to have “proven” the earth is flat. It is just on a whole other level from whether a character is a believable 6th-grader.

That said, *eventually* it didn’t bother me either. For me, the constant parallels between the Pi story and the boys’ journey became so increasingly direct and improbable that I had to either 1) give up enjoying the book at all or 2) pivot and read it as a piece of magic realism, a fantasy Odyssey where there could be narrative numbers that parallel lives and may or may not end. I doubt it was really the author’s intent to write a straight piece of historical fiction given the choices she made. The problem is that the beginning just reads so convincingly as realistic historical fiction. Writers like Vanderpool and Gary Schmidt do such a good job setting their novels in a historical time that it’s hard not to demand verisimilitude in other respects. (I’m one of those who thinks Okay for Now is stratospherically good, but I read it as essentially escapist like Dickens not realistic.) Not that they should be let off the hook. Just four words on the first page of When You Reach Me, “Just like you said,” was enough to clue the reader that this won’t be just about middle school friendship in 70s New York.

Having read Hokey Pokey, The Center of Everything, and Navigating Early in quick succession, I have to wonder, what is with all these stars/constellations as key framing devices? Coincidence? And not that anyone asked, but currently The Center of Everything is my favorite, I much preferred Hokey Pokey to Doll Bones, and I think P.S. Be Eleven does suffer in more than one respect from being the sequel to the magnificent One Crazy Summer.

“Or it would be like having a professor character make a serious claim to have “proven” the earth is flat. It is just on a whole other level from whether a character is a believable 6th-grader.”

Oh, I love this! It’s exactly how I’m going to explain the problem to people in real life from now on, both in showcasing how much of a completely strange choice the pi thing is and the ways in which it is a problem for me, but might not be a problem for someone who wants to focus on a different aspect of the book.

Jonathan, your phrase, “And I find autistic narrators so yesterday”, sounds a trifle ableist to me. And quite frankly, a little offensive. Would you mind clarifying? Thanks.

Kelly,

if Jonathan pointing out that the autistic narrator is becoming a trite device is ableist, I can’t wait to hear your thoughts on THE REAL BOY…

Well, that’s kind of beside the point. We’re talking about THIS bit of snark about THIS particular book – and the reviewer unintentionally revealing the blindness caused by privilege. And that’s an important thing to notice. What I was trying to point out was that the comment itself “I find autistic narrators so yesterday” to be offensive because it assumes that there is a limit to contribution of autistic voices or points of view into the larger canon. And I reject that idea. And honestly? Can you imagine inserting any other class of people into that sentence? If autistic narrators are “so yesterday”, what about gay narrators? Or Asian narrators? Or females? Or blind people? Or people with HIV? It’s a little offensive, don’t you think?

Now, that doesn’t mean that he can’t critique the book on its merits – clearly he should. That’s the point of this blog. But to denigrate a narrator (“so yesterday”) with that kind of snark is to say to Autistic people everywhere that there is a limit to how often this reviewer is willing to listen to their voices. That their experience only *sort of* adds to the symphony of the Human Experience that Literature seeks to explore, unpack and uplift. And you know what? As a human being who loves a lot of human beings who happen to be on the Autism spectrum – and who values the experience and knowledge and capacity for wonder and heartbreak and joy of every human being on this whole blessed planet regardless of their neural make-up – well. I take issue with it. Very much so. And so should you. And it is disappointing to see a comment like that on a blog dedicated to the best in books – one that should seek to elevate instead of degrade. And I think a retraction is in order.

Well, Jonathan invited me to reiterate my objections. I will try to not go on and on.

Yes, it’s a decent story. But if the rowing part were described in such a way that the boat wouldn’t even float, would you give it an award? The math part is like that for me.

This is not how mathematical proofs work. Not at all. Not even close. Pi was proven in 1741 to be irrational. A math professor in the 1940s would never seriously conjecture that it is not irrational. He also would have submitted it to a journal, with some vetting from colleagues (who would have quickly laughed it out as an April Fool’s joke. Or something.) What’s more, his “proof” could not possibly depend on whether the derivation of pi was correct, so Early correcting that couldn’t possibly change his results. You don’t base a proof on the patterns already calculated. That’s not how it works. And he would have checked and had his friends check what was calculated if he *were* basing something on that. (Mathematicians are notoriously collaborative.) It just. doesn’t. work.

Now, this whole thing about pi “ending” didn’t have much to do with Early’s quest. I wish it had just been left out. See pi as a story? Okay. Though why she couldn’t use the actual digits of pi when they’re readily available, I have no idea, but whatever.

But the part where the adult shakes his head that he just doesn’t understand — that mathematical proofs are just mumbo-jumbo for smart people? Oh, I don’t like giving that message to kids.

I like Leonard’s illustration. This is an error on the level of saying a baseball game has 4 innings. There is NO WAY it would have happened. Kids probably won’t know that — which to me, makes it much worse.

” And I find autistic narrators so yesterday, but again, it didn’t matter here…” I had to read that several times to make certain I wasn’t misreading it or misinterpreting.

Is this kind of sentiment actually… acceptable? Substitute any other group of people who are differently abled and I wonder if you would have felt comfortable writing that.

I agree with Leonard ninety-nine percent! His post mirrored my thoughts exactly, except the part about preferring Hokey Pokey to Doll Bones. That’s crazy.

I read Navigating Early quite soon after its release so I will refrain from commenting about any of the faults outlined in the earlier comments here. I would need to do a reread before responding with intelligence. What I do have to agree with is Kelly Barnhill’s statement. I find the comment “And I find autistic narrators so yesterday, but again, it didn’t matter here.” to be insensitive and hurtful. I find that the voice of every single child is just as important as another’s voice; then, now and always. Quite frankly I am astonished and more than a little bit angry.

As I read this review, I cannot get past the phrase, “And I find autistic narrators so yesterday.” Wow. Excuse me if I find this phrase offensive and irresponsible. Autism is something that has been in the shadows for so long. Shouldn’t we celebrate the fact that it is coming out of those shadows and people are finally gaining a better understanding of what it is like to have autism and to be misunderstood most of your life? It is too bad that this has the ability to dampen your reading enjoyment. I have seen in my classroom the empathy that comes after reading such a book when a child finally understands what a classmate is going through. Perhaps one could grow tired of books narrated by women or any other group that has been considered a minority. Would it be acceptable to find these narrators “so yesterday?” I think there are times when one should choose their words carefully and consider their impact. This is, I believe, one of those times.

I liked this one okay, but it is in no way a favorite. I see the problems with the Math proof as being something too wrong for the field to just let slide (And like Sondy I just don’t get why she needed to change the digits of Pi in the first place-though that is minor in comparison to the bigger issue of the proofs.)

That issue aside. I really loved Early as a character, but had some issues with Jack’s voice. For a first person narrative, I felt that author intruding far too much. The overwrought language would have worked had it been 3rd person, but coming from Jack it just sounded…wrong. As smart as kids are there are some things that they are not going to think about in certain ways. And I don’t have the book handy so can’t point to specific quotes, but it the voice just felt too old and with too much experience. Not the sort of I-have-seen-too-much-of-life-and-am-older-than-my-years type, but real genuine years of experience.

The coincidences at the end were too much for me, but that could be because I was already annoyed by that point with the voice and the Math stuff.

I’m sorry to hear that you find autistic narrators to be “yesterday” since I have little choice but to continue writing them today and tomorrow.

Tom “write what you know” Angleberger

Oh, dear. Let me clarify. Some people have read my comments as a value judgement on autistic people and/or the need for them to be represented in literature. That was not my intention at all, and I have only myself to blame for the miscommunication, which was further exacerbated by my flippant tone. I have worked extensively with special education students in general, and autistic students in particular. I have been a classroom teacher at a full inclusion magnet school, the librarian at a special education magnet school (which included several autism classes), and a special day class teacher.

I was speaking about the autistic narrator purely as a literary trend (which, in relation, to NAVIGATING EARLY is inaccurate, I believe, because Jack doesn’t fall on the spectrum, but rather Early). The dramatic increase in autism in recent years is obviously reflected in the current literature, but I would also add that most–if not all–of the books came after THE CURIOUS INCIDENT IN THE DOG IN THE NIGHT-TIME was published in 2004–and since then there have been several prominent books every year with either an autistic narrator or autistic characters. It’s hard not to view it as a trend. This year there are no less then three high profile books that we will likely consider here: NAVIGATING EARLY, THE REAL BOY, and COUNTING BY 7s.

I wouldn’t say that autistic characters are overrpresented because you can never have too many portrayals of a minority, especially good ones. But I do question if they are disproportionately represented in relation to other disabilities, and my comment was an unfiltered response to that trend. I’ll gladly strike the offending comment from the post. I’ll be out of town this weekend, so it’s possible that I won’t be able to respond to further comments until Monday.

I don’t think the comment should be retracted (though maybe reworded.) I think there’s a discussion here worth having in the context of Navigating Early and its Newbery-worthiness. My oldest son has an Asperger’s diagnosis. Telling people sometimes helps them be more patient with him. But sometimes, with grownups more than kids actually, it becomes a stumbling block. They hear the word, and suddenly they think they know all about him. Even with professionals, sad to say. They will tell us, “you can expect this,” or, “he will be like this.” How would they know? The miracle of my son, like all children, is that he is always surprising and confounding expectation. (It’s a bit like Dwight at Tippett Academy in the third Origami Yoda book. The people there call him “special” and proceed to treat him exactly the way they treat every other “special” kid. They can’t bother to get to know him.)

So in her author’s note, Vanderpool writes, “the idea of writing a story about someone with an unexplainable gift stayed in my head.” This comes dangerously close to an attitude that I think Jonathan’s remark was pushing back at. It’s possible a writer could learn about autism and think, “oh, that is so interesting. Writing about someone like that would make a good story.” No thanks. I want stories about *someone* not *someone like that*. Fortunately, Vanderpool later writes, “Early is not meant to be a representation of an autistic child. He is a unique and special boy…” Good for her.

But did she succeed? Honestly, sometimes Early did come across more as a type than an individual. Billie Holiday on rainy days. One place where I think Vanderpool did pretty well is the scene when Early tells “Pauline” she has a pretty smile. It is both consistent and surprising. (But far less surprising because telegraphed by the Pi story. What if the book had the Pi stuff came after the boys’ stuff? It’d be different, sure, but hard to say better or worse.) Surprising because this not the behavior of a stereotypically autistic boy. Consistent because he is following his story, his “unexplainable gift”, which here gives him a capability beyond typecasting and connects the “unstrange” reader to him, for who hasn’t discovered capabilities and how to live from stories and books?

I can say I have much to add to the discussion. NAVIGATING EARLY’s strengths for me lie in the episodic plotting, the visceral settings, and the engaging characterization of Jack and Early. If the fluttering strands of the story tie up a little too tidily for it not to be contrived then that is a serious flaw. When I read it, oh so long ago, it seemed that Vanderpol had left enough footprints for everything to come together in a believable if farfetched manner. I’d need to read it again to make a more passionate case.

I will need to take the experts word on the Pi stuff. In a million years I would never have known the subtext, or bothered to pursue it. I will admit to skimming through the pi stories as they held little interest. I would guess the committee would need to consider the inaccuracy.

(In a parenthetical comment over Jonathan’s comment that has turned into a civil-liberties hullabaloo. First of all, to tag Jonathan as insensitive to people with disabilities is silly and ironic. There has been an influx of books in children’s fiction with autistic characters and narrators in recent year. This is not good, bad or unnecessary. I feel, however, a few of them (not Early) have been more exploitative than illuminating. An author should write the story and characters that move him. Myself, I’d love to see more character with disabilities and a wide variety of races show up in children’s literature without their race or disability taking center stage in the story. I would love find the Native American Beverly Cleary or the Encyclopedia Brown with muscular dystrophy.)

Um, I also meant to say that I don’t believe autism is a disability so much as a different way of navigating the world. I was once told that to know one autistic child is to know one autistic child. I’m often surprised when I’m told which of my students are on the spectrum.

I fell for the beginning of the book – the tone, setting, characters, etc. – but I started to drift off when it came to the Pi sections. I didn’t find the plotting of those sections compelling, although I wasn’t bothered by the coincidences. I’d read Sondy’s objections before starting the book, and agree that they’re bothersome in a way that changing Joe Pepitone’s activities is not. By the time I got to the end, I felt like the whole thing dragged a little bit, and frankly the ending was unmemorable. But the beginning? I can understand why some people love it, even though it feels too flawed for the Newbery to me.

I think maybe I just don’t “get” Clare Vanderpool. I’m on the record as being not a big fan of Moon Over Manifest, and this one felt utterly artificial to me. I never bought Early as an actual character, rather than an aggregation of literary quirks, and I was really, seriously bothered by the math errors and the fact that the story doesn’t use the actual first hundred(s) digits of pi. This wouldn’t make my top 20 books of the year, though I will concede that the setting is well done.

I think Jonathan’s being “over” autistic narrators is due not to prejudice but to the way these narrators are used to gussy up what can be pretty ordinary stories otherwise. Plus, there is a tendency to make autism “interesting” in a way I find patronizing, and that I have seen before with children’s book characters who have synesthesia or OCD or, back in the day, were deaf or blind. The deaf kid’s hands “moving like beautiful butterflies,” the blind kid’s supernatural sense of smell that alerted everyone to the fire in the cabin down yonder, etc. We don’t much see books like these anymore because we, like Jonathan, “got over it” and moved on to portrayals that were truer and more respectful.

In addition to the good points made by Leonard and Roger, I’d also mention that . . .

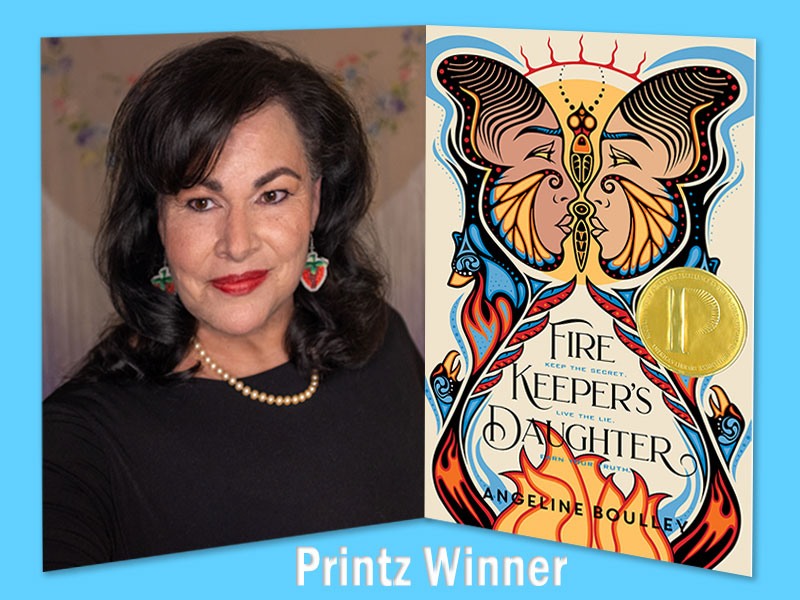

1. No other disability has gone mainstream quite the way that autism has. AL CAPONE DOES MY SHIRTS and RULES both won Newbery Honors. MOCKINGBIRD won the National Book Award, and THE REAL BOY was just longlisted. THE WHITE BICYLE won a Printz Honor. And THE CURIOUS INCIDENT OF THE DOG IN THE NIGHT-TIME won big prizes, too. And these are just the high profile titles. Can you think of another disability with this kind of a literary track record? Would it be inaccurate to say that autism is trendy–or does that carry a negative connotation?

2. There is an unabashed emotional quality to books which feature disability in general (WONDER, anyone?) and autism in particular. It’s human nature to respond to this–how often have Oscars gone to portrayals of handicap/disability/mental illness? When you take that inherent tear-jerking quality and couple it with an incredible voice the way that Haddon did in CURIOUS INCIDENT you create something really special. The problem is that it was fresh when Haddon did it, but the more often it gets done (and done less skillfully), the less it feels distinct and authentic and special–which is not meant to curb or undermine the portrayal of autism.

3. I’m not going second guess why authors write the books they do. I think the unique voice of an autistic narrator and the potential heartwarming qualities of a story may be contributing factors, but I don’t think they are necessarily the main reason. Still, if there are aspiring authors out there looking for a challenge, why don’t you take up this one:

http://www.hbook.com/2013/08/choosing-books/horn-book-magazine/sign-in-print/

If you are talking about books about characters with autism as “portrayals that (are) truer and more respectful” versus using a narrator with autism as a way to “gussy up what can be pretty ordinary stories otherwise,” (both quotes are from Roger Sutton’s comment) then, yes, that is a conversation I’m interested in reading about. (I read this blog and children’s literature religiously but do not usually participate in the blog discussion.) But when you use “inherent tear-jerking quality,” “trendy,” “disability gone mainstream,” well, that is when I find your argument condescending and insensitive.

As more and more young people are diagnosed with autism every year, it makes sense to me that more books with characters with autism are being written. And, please. Consider ALL the books that are published each year… books containing characters with autism are still quite few and far between. (Important: quirky does not always equal autism!)

I think your assertion (and perhaps I’m inferring here) that “aspiring” writers choose to write characters with autism as a “challenge” is cynical and depressing… as if writers write a characters with autism because they are hoping to capitalize off of some “trend”. We aren’t talking about love triangles. Autism isn’t a literary device. Is it possible some authors are writing characters with autism, badly? Yes. Is it possible *some* authors are writing characters with autism because they think characters with autism are award-bait? Um, gross, but possible, I guess. But why not talk about each book, case by case instead of lumping them together? If you DO come across a book that treats characters with autism inauthentically and gratuitously, I’d be more than happy to read THAT specific criticism. (And I’ve read posts/comments here in the past that argue that case…) Please don’t, though, dismiss the well-written ones… which you probably don’t feel like you are doing, but when you use the word “trendy” to describe a disability in literature, it *feels* like you are.

I feel like I’m in some kind of bizarro world in this thread and people keep attributing things to me that (a) I did not say and (b) I do not believe.

Did I not say that autism is NOT overrepresented, that we can never have enough positive portrayals of a disability experience? I did. Go back and read my earlier response. But I also said that it is disproportionately represented in relation to other disabilities–and I just offered up six excellent autism titles to prove my point. Show me six high quality, high profile titles on any other disability in the past ten years. I dare you to prove me wrong. I have a nephew and niece with Cystic Fibrosis. I’d love six titles on that please. Another niece with frequent seizures which have resulted in visual impairment, delayed speech, coordination problems, and a host of other issues. Six more titles please. I never said we have enough autism titles, but why do we have so many compared to other disabilities?

Not only are you “inferring” in your final paragraph, but in anticipation of your comments I patently disavowed them. Go back and read again, please. We do both things here on this blog: we discuss general trends in the field of any given year and we discuss individual books. Did I not also promise further discussion on THE REAL BOY and COUNTING BY 7s? If you really read this blog regularly, haven’t you seen that?

I can’t speak as to why more authors don’t feel compelled to write about characters with CF. I’m merely reacting to your words that books with characters with autism are “so yesterday” and the like. You say characters with autism are not overrepresented. But then say they ARE overrepresented compared to other disabilities… instead of just saying, independently, characters with differences are underrepresented. I’m not trying to tell you what you believe. I’m simply trying to explain why I and others are reacting the way we are to what you are actually writing.

In my last paragraph I was responding directly to this comment:

“1. No other disability has gone mainstream quite the way that autism has. AL CAPONE DOES MY SHIRTS and RULES both won Newbery Honors. MOCKINGBIRD won the National Book Award, and THE REAL BOY was just longlisted. THE WHITE BICYLE won a Printz Honor. And THE CURIOUS INCIDENT OF THE DOG IN THE NIGHT-TIME won big prizes, too. And these are just the high profile titles. Can you think of another disability with this kind of a literary track record? Would it be inaccurate to say that autism is trendy–or does that carry a negative connotation?

2. There is an unabashed emotional quality to books which feature disability in general (WONDER, anyone?) and autism in particular. It’s human nature to respond to this–how often have Oscars gone to portrayals of handicap/disability/mental illness? When you take that inherent tear-jerking quality and couple it with an incredible voice the way that Haddon did in CURIOUS INCIDENT you create something really special. The problem is that it was fresh when Haddon did it, but the more often it gets done (and done less skillfully), the less it feels distinct and authentic and special–which is not meant to curb or undermine the portrayal of autism.

3. I’m not going second guess why authors write the books they do. I think the unique voice of an autistic narrator and the potential heartwarming qualities of a story may be contributing factors, but I don’t think they are necessarily the main reason. Still, if there are aspiring authors out there looking for a challenge, why don’t you take up this one:

http://www.hbook.com/2013/08/choosing-books/horn-book-magazine/sign-in-print/”

Again, I’m not trying to tell you what you believe. You seem genuinely puzzled as to why what you’ve written is offensive to people. You wrote, “Would it be inaccurate to say that autism is trendy–or does that carry a negative connotation?” The answer is YES. Yes, it carries a negative connotation to say “autism is trendy.” It carries a negative connotation to say that it characters with autism are “so *yesterday*” (emphasis yours). It carries a negative connotation when you say “No other disability has gone mainstream quite the way that autism has… Can you think of another disability with this kind of a literary track record?” To me, anyway.

You write: “We do both things here on this blog: we discuss general trends in the field of any given year and we discuss individual books. Did I not also promise further discussion on THE REAL BOY and COUNTING BY 7s? If you really read this blog regularly, haven’t you seen that?” Yes, I do look forward to the discussion of both… and about THE REAL BOY, in particular, as I loved BREADCRUMBS. I suppose I could mention that you implying that I’m only here as a whacky Autism Advocate! and that I’m lying about being a regular reader is offensive, but you didn’t really SAY that, did you?

All right, I’ve been trying to stay out of this conversation, but I think I really need to come to Jonathan’s defense here.

The main problem with the arguments I see here are that they fail to distinguish between autism as a real world syndrome and autism as a “literary device”. DPatermorrow says “Autism isn’t a iterary device”. Um . . . yes, it is. Anything that an author uses to construct his or her narrative is a literary device. Failing to realize that leads to these arguments:

DPatermorrow: “But when you use “inherent tear-jerking quality,” “trendy,” “disability gone mainstream,” well, that is when I find your argument condescending and insensitive.”

“The answer is YES. Yes, it carries a negative connotation to say “autism is trendy.” It carries a negative connotation to say that it characters with autism are “so *yesterday*””

Jonathan wasn’t saying that autism as a real world syndrome is “trendy” to have, or “inherently tear-jerking” when we encounter it *in the real world*. He was saying that using autistic narrators (ie, using the literary device) is a tear-jerking move, in the same way that actors choose disabled characters to play in order to win Oscars, etc. and that the concept of using autistic narrators has become “trendy”. These are not value statements about “autism”– they are possibly falsifiable claims about the use of autism in literature. You don’t think it’s become trendy, or authors use it for its tear-jerking (or whatever) qualities–come up with some evidence. I think Jonathan’s point about the number of high profile books in recent years using autistic narrators is a strong piece of evidence that this has become a go-to trope, possibly even “trendy”. But that has nothing to do with making value statements about people with autism as a whole.

Personally, I don’t happen to agree with Jonathan’s burn-out on seeing so many books with autistic narrators, but I can certainly understand it (and he’s almost certainly read more of them than me). But importantly, it is possible to disagree with that opinion without painting Jonathan as condescending and anti-autism.

Um, yes. I *know* Jonathan wasn’t saying that autism as a real world syndrome is trendy to have.

I can read this kind of criticism “in this book, the use of an autistic narrator feels inauthentic and gratuitous… I feel that the author is merely playing on my sympathies,” as long as it is backed up by examples from the book, and not get too worked up, even if I completely disagree with the opinion.

But, when commenting on a book where the reviewer thinks the character with autism IS written well and that the story feels authentic, the reviewer says “and I find autistic narrators so yesterday, but again, it didn’t matter here…” well, yes. That bothers me.

Not once did I say Jonathan was making value statements about people with autism. “He was saying that using autistic narrators (ie, using the literary device) is a tear-jerking move, in the same way that actors choose disabled characters to play in order to win Oscars, etc. and that the concept of using autistic narrators has become “trendy”.” THIS is what bothers me. What, it isn’t possible that a writer just might have an important story to tell involving a character with autism? If you see an specific example of an autistic character being used inauthentically, sure, point it out and back up your claim. But to make this generalization is, I think, reckless. And this blog’s sphere of influence is… well, I don’t know what. But, again. A little more thoughtfulness would be appreciated.

(And, by the way, when I wrote “autism isn’t a literary device,” I was contrasting it with love triangles. I think the discussion of the use of characters with autism in a novel should be done a little more sensitively than one might discuss foreshadowing or red herrings.)

Well, forgive my exasperation, but the whole point of this entire post is to examine a specific book rather than a general trend (or pattern or whatever you want to call it so that it doesn’t offend). My initial comment was meant to open discussion of Early’s autism and set the stage for us to compare and contrast that with THE REAL BOY, COUNTING BY 7s, and possibly AL CAPONE DOES MY HOMEWORK as a sub-discussion of whether or not these books are distinguished.

As a voracious reader, I do become snarky and impatient with so many things that wouldn’t bother me if I didn’t read quite so much of it. I think that’s human nature. When you couple that with a subject that can easily be manipulated and exploited (Holocaust fiction has this tendency for me, too) then it can exacerbate my frustration. And the more of a certain kind of book there is, the harder it is for newer books of the same ilk to stand out as distinguished. That is to say, that any new books with autism are subconsciously judged, in my mind at least, against the aforementioned books. The Newbery process doesn’t allow that comparison, however–and it doesn’t allow for my snarky comments either. It’s all part of the process of divesting ourselves of baggage to more objectively consider the books before us.

I knew that by wading back into this discussion that the conversation might turn from NAVIGATING EARLY and autism books to me. I hoped that wouldn’t happen, but I do think this conversation is an important one to have. I’m going to bow out of it now, and let you continue it without me, but I’ll see you in a future thread.

excellent discussion all the way around—invigorating to read such articulate and civil expressions of variant points of view—I identified with some parts of all viewpoints—which is exactly why I read this blog—makes me think more deeply, less judgmentally, and with more diverse awarenesses about the books reviewed—can’t wait to get my hands on investigating early—armed with all o’ y’all’s cautions for sensitivity—-a grateful reader from georgia—-