When Green Becomes Tomatoes

I was pleasantly surprised to see WHEN GREEN BECOMES TOMATOES tied with WOLF HOLLOW atop our recent Top Five tally. We liked Fogliano’s previous books, AND THEN IT’S SPRING and IF YOU WANT TO SEE A WHALE, but being picture books, they were somewhat of a hard sell.

I was pleasantly surprised to see WHEN GREEN BECOMES TOMATOES tied with WOLF HOLLOW atop our recent Top Five tally. We liked Fogliano’s previous books, AND THEN IT’S SPRING and IF YOU WANT TO SEE A WHALE, but being picture books, they were somewhat of a hard sell.

This longer work, a poetry collection, should be easier to build consensus around. I’ve long thought there was some truth to the adage that a chain is only as strong as its weakest link, at least when it comes to evaluating collections of poems or stories. Some things in a collection everyone can agree are strong, others draw a mixed response, and then too, yet others elicit no strong responses from anybody (anybody in the room, at least). Uniform strength of a collection is a factor, but only one. This book, however, with its untitled poems under a series of dates throughout the year feels as much like a journal as it does a collection, and thus I feel less inclination to judge the parts of the whole, but rather as a single entity. Actually, the division of the year into four seasons encourages us to compare poems within each season and against the entire year.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Fogliano’s style is recognizably distinct. She uses free verse that eschews capitalization and punctuation, relying wholly on line breaks, occasional parenthetical insertions, and a healthy dose of repetition to create a pleasing rhythm and cadence. She also employs strong imagery, rhyme, and a whimsical, philosophical touch that perfectly captures our human curiosity about the world around us. Fogliano’s poetry speaks to young and old alike.

There are so many good poems in this collection. I’ll cite one of my favorites below, and will invite you to do likewise in the comments–in addition to the usual discussion of the strengths and weaknesses of the book.

september 10

a star is someone else’s sun

more flicker blow than blinding

a speck of light too far for bright

and too small to make a morning

This poem is a master class in consonance (the repetition of consents; alliteration is when that repetition comes at the beginning of the word) and assonance (the repetition of vowel sounds).

Let’s look at consonance first.

S: september, star, someone, else’s, sun, speck, small.

R: star, more, flicker, far, for, bright, morning.

F: flicker, far, for

B: blow, blinding, bright

L: else’s, flicker, blow, blinding, light, small

T: 10, star, light, too, bright, too, to

M: someone, more, small, make, morning

N: someone, sun, than, blinding, and, morning

K: flicker, speck, make

G: blinding, morning

Z: is, else’s

The only consonant sounds unaccounted for are the “p” in speck and the “d” in and. Everything else is a combination of the consonant sounds listed above, and I would say that there are only a half dozen that are really dominant throughout (S, R, L, T, M, and N).

Now on to assonance. The best way to get a sense for this is to read aloud only the vowel sounds as they are pronounced in the word in which they appear.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

In the first line you have four schwa sounds: a, both vowel sounds in “someone,” the second one in “else’s,” and sun. There is a short i sound in “is,” a short e sound at the beginning of “else’s,” and the short o sound in “star” (which is an r-controlled vowel). The repetition of the schwa sound is pleasing to the ear, but the contrast of the other vowel sounds (which are often spelled in alternate ways) also make for good prosody. I can break down the vowels in the entire poem, but it’s probably overkill. We can continue the conversation in the comments if there is interesting in doing so.

There are some instances of rhyme in this poem, but it’s really the repetition and slight variation of consonant and vowel sounds that make this such fun to read aloud. Nitpick: I think the poem reads aloud better if the “and” in the final line is dropped.

For all it’s rich language, the content of the poem is striking too. It’s a poem about perspective. Taking a familiar object such as a star in the summertime sky, and allowing the reader to see it in a different light. Does it resonate with you beyond that simple fact? What does this poem contribute to the Summer section? What does it contribute to the book as a whole? These are additional questions to ponder.

Most distinguished contribution to American literature for children? I think you can build a very strong case off this single poem, and I think there are at least a dozen more, possibly two, that are just as rich. What do you think?

Filed under: Uncategorized

About Jonathan Hunt

Jonathan Hunt is the Coordinator of Library Media Services at the San Diego County Office of Education. He served on the 2006 Newbery committee, and has also judged the Caldecott Medal, the Printz Award, the Boston Globe-Horn Book Awards, and the Los Angeles Times Book Prize. You can reach him at hunt_yellow@yahoo.com

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

One Star Review, Guess Who? (#202)

This Q&A is Going Exactly As Planned: A Talk with Tao Nyeu About Her Latest Book

Exclusive: Giant Magical Otters Invade New Hex Vet Graphic Novel | News

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

Take Five: LGBTQIA+ Middle Grade Novels

ADVERTISEMENT

Favorite book for children this year, I think. I love the organization, the way the text works with the illustrations, and the full-circle aspect of it, tying in with the nature of the seasons. Really eloquent, and well done.

Thanks for the deeper look at this. I use IF YOU WANT TO SEE A WHALE every year to introduce alliteration to my first graders. She is such a master of words and how they sound bumping up against each other. TOMATOES is rarely on the shelf for me to get another look at, with my students clamoring to get their reading in. I don’t think it is really a Newbery criteria thing, but I remember another strength of this book being the organization of the words on the page. Such a clear delineation for the eye to follow the progression of the year.

This is my top pick this year, and I think it is very likely that the Real Committee could build solid consensus around it. I rarely think writing is unimpeachable, but I am hard pressed to find anything negative to say about Fogliano’s beautiful way with words. Even the weakest poem in this collection (the one about pumpkins) is so strong in its use of meter and rhythm that I cannot knock it more than just saying “not for me”.

Really, though, this book is positively brimming with gasp-worthy use of language – subtle, quiet, lovely observations with gentle imagery, wondrous word choice, and a great sensitivity toward children. There is one poem in July about a firefly visiting in the middle of the night that is probably one of the best poems I’ve ever read. As Kristin pointed out above, the full-circle aspect is particularly pleasing. I breathed a satisfied sigh when the final poem was exactly the same as the first.

Top marks all around. And I wouldn’t have ever read this book had it not been for Leonard and Mr. H’s enthusiastic recommendations. So thank you, guys.

I have some thoughts/musings about how this poetry collection holds up against the Newbery criteria and how it may fare in discussion. Is the narrator of the poems a well delineated character? Does the progression through the year constitute a well-developed plot? Is the setting vague?

I would say this book is definitely doing an excellent job exploring themes (nature, seasons, change and the emotions elicited thereby). It is definitely excellent in terms of style. It is clear and well organized.

The terms and criteria tell us: “Because the literary qualities to be considered will vary depending on content, the committee need not expect to find excellence in each of the named elements. The book should, however, have distinguished qualities in all of the elements pertinent to it.”

So are plot, character, and setting pertinent to this book? Maybe you argue they are *not* pertinent to a poetry collection. Maybe you argue that the book is so excellent in terms of its other elements that it outweighs weakness in plot, character, and setting.

I’m sure some will argue that this book actually has a strong character, strong plot, and a strong setting. But, as someone who reads for character and plot and setting, I found this book kind of boring.

Hi Destinee,

I am one of those who would “argue that this book actually has a strong character, strong plot, and a strong setting.”

Setting: In an earlier post, Brenda Martin questioned whether the setting was so specifically evoked that certain readers might feel excluded. We would have to weigh how much of this is coming from the illustrations, but this argument suggests this book does do a distinguished job in establishing setting for the reader. I certainly felt “in the place” of whatever Fogliano was writing about, whether in the rain or at the beach looking out or in my comfy chair.

Character: Maybe it is just the distinct, strong authorial voice, and maybe the “character” is just some version of Julie Fogliano the poet herself, but I “felt” a strong character here, in the sense that the voice coming through here seems human and real and complex and sympathetic.

Plot: Nothing original to say here. For me too, the marriage of the poetry to the progression of seasons left me “plot”-satisfied.

Why would anyone read WHEN GREEN BECOMES TOMATOES specifically for character, plot, and setting? It’s a collection of poetry. I think it needs to be analyzed as such. You can’t knock a book for what it isn’t. That’s not relevant to Newbery discussion, correct?

The way I interpret that section of the criteria you pointed out, WHEN GREEN BECOMES TOMATOES holds up well. It is highly distinguished in the areas pertinent to it (theme, style, and setting).

Usually I’m a bit ho-hum abut poetry, but these are so beautiful. Looking back at some of the poems, I will stand up and cheer if this wins. I agree with Mr. H — why would we count against a poetry book for not being a novel?

Here’s a short one which so quickly establishes the setting while using language so skillfully, and keeping with the theme of seasons.

june 15

you can taste the sunshine

and the buzzing

and the breeze

while eating berries off the bush

on berry hands

and berry knees

This is another great example of consonance and alliteration being a hallmark of this book.

I love how the BUH in “buzzing” bounces off the SUH in “sunshine” (and then the ZEH in breeze bounces off the ZUH in “buzzing” – you can follow the sounds throughout the poem’s pogress). The playfulness of the metered syllables are almost songlike in their quality – 7, 4, 3, 8, 4, 4 – you can almost hear the melody.

It’s simply a Master’s class in poetry. This is innate talent at hand.

I think what I’d need to know to get on board with this book is that there are actual kids out there who love it and connect with it. Unlike DaNae’s, my library does not have kids clamoring for beautiful poetry about the seasons. If I were on the Newbery this year, I feel like I’d have to do some serious pleading/bribing to get my book club kids to read WGBT. But I know the important question is not, “Are kids excited to read this?” but “How do kids react to it after they’ve read it?”

This is a fair criticism. I think Fogliano’s writing is astonishing for being both literary and accessible to a young audience. But that in itself may not be enough to satisfy some interpretations of “excellence of presentation for a child audience.” I think the strength of this book is its “richness”, and the appeal of this book may rely on a reader’s ability to plumb its depths. Some of the testimony here suggests this book may shine to best effect in a classroom setting, with a facilitator like Jonathan or DaNae who can show the child reader just how rich a text like this is. Done right, this could inspire a lifelong appreciation of poetry. But perhaps the unassisted child reader may not see all the “there” that’s there.

The criteria of course say the award is not for popularity. Nevertheless, I think Destinee’s perspective shows there is a possible take on “excellence of presentation” that may not align with a book like this.

Okay, I don’t want to misrepresent. I feel certain that the reason this book is hard to keep out the hands of my students has more to do with its brevity. They need to finish five books before they can vote and why not choose one that can be read in an hour, unlike THE GIRL WHO DRANK THE MOON.

Forgive me if I’m wrong about this, Destinee, but when has a child’s reaction to a book ever guided the committee’s decision? Jonathan, when hosting discussion, often reminds us of this. And you cannot *posssibly* gauge whether children will like a book. No two children are alike. Some may love WGBT and some may not.

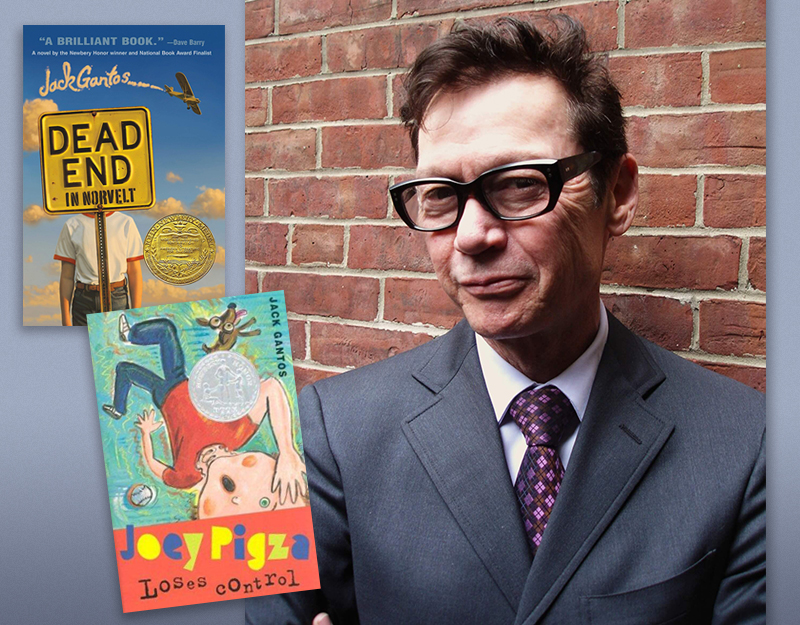

Because truly – if children liking a book ever factored in to the Newbery committee’s decisions, we wouldn’t have books like Good Masters! or Dead End in Norvelt winning. Rick Riordan would win every single year.

Joe, I think it’s *vital* to talk to child readers when you’re on the Newbery committee. How else can you truly judge excellence of presentation for a child audience? I’m not saying one child stands in for all children. I’m not saying it all comes down to whether or how much individual children enjoy the book.

But I am saying that it’s possible to gauge how children respond to a book. You just have to have access to children and books. (When I fill out my ASLC ballot I tend to vote for folks who sound like they can/will talk to actual children about books.)

A book doesn’t have connect with every child. But I don’t know how you adequately prepare for your Newbery discussion without talking to children about the books. The manual says:

Prepare for committee service by: reading the background material, taking part in book

discussions, speaking to community groups, faculty meetings, PTAs and individuals about

currently published books and about the history of the awards…

To me, the “speaking to individuals about books” includes kids.

I do think child feedback is critical to understanding how well a book works for its child audience. A perfect example for me is SAM & DAVE DIG A HOLE. You really have to read that book to a group of children to appreciate its magic. I see occasional reviews here and there where it didn’t go so well with an individual child, and I completely get that. Context is key.

That said, too often I think adults hide their own feelings about a book behind a child response or an alleged child response.

Destinee, but that’s really not quite what you wrote in your initial post. You wrote two things that struck me as rather curious:

1. “I think what I’d need to know to get on board with this book is that there are actual kids out there who love it and connect with it.”

How can we *possibly* know what kids are going to like – especially when much of the Newbery canon is not, generally, what the majority of kids rush for? They generally indeed love Rick Riordan. But The Evolution of Calpurnia Tate? Where the Mountain Meets the Moon? These books can take a major sell. In my school, a majority of those kids are either unimpressed or bored by those book; conversely, a minority of them love the books and connect deeply with them. We could literally make that argument for every book published in a given year. I can’t *imagine* a Rick Riordan or James Patterson book making it to the final table for serious literary discussion. That would be like the Pulitzer committee discussing a Jodi Piccoult novel. And how many adults read mainstream, bestseller fiction more than Pulitzer literature?

2. “If I were on the Newbery this year, I feel like I’d have to do some serious pleading/bribing to get my book club kids to read WGBT.”

Don’t you think this statement is true for books like Good Masters, A Single Shard, and even Echo? At 600 pages, it took quite a bit of convincing and cajoling for me to get my middle school Mock Newbery kids to read Echo. When they did read it, they enjoyed it and it eventually placed second last year in our votes. But, honestly, in the past 8 years as my school’s librarian, I have YET to have a student gush about Good Masters (or Criss Cross or Higher Power of Lucky or Dead End in Norvelt). Most of the kids who did check those books out had to be cajoled into doing so (or had to read a Newbery book for a class assignment).

Nowhere in my response did I say you shouldn’t talk to children about books. No librarian worth his/her salt fails to talk to children about books. But a Newbery committee member certainly wouldn’t take children’s favorites back to the table and say, “Well, guys, my student really love this Gordon Korman/Pseudonymous Bosch/Lemony Snicket/Meg Cabot writer, so we should really consider them this year!”

“If I were on the Newbery this year, I feel like I’d have to do some serious pleading/bribing to get my book club kids to read WGBT.”

I’m not sure I agree with this statement. As DaNae pointed out, the book can be read very quickly and kids like that. Gives them a sense of accomplishment. It has nice illustrations too. I really don’t believe you’d have to twist the arms of book club kids, kids who already tend to like to read, to read this book. Add in a little conversation, and I truly think you’d find kids appreciate the book too. Have you tried or are you just projecting?

And it is a little strange to me, that we’re questioning whether or not kids will like this book now, when the Newbery canon consists of so many titles that many kids can’t relate to at all! I just flat out don’t see this as an issue with WHEN GREEN BECOMES TOMATOES.

The way I interpret the Newbery criteria, the award should not be given to a book that doesn’t engage its intended audience. WGBT strikes me as a book kids might find boring. Frankly, I suspect this *entirely* because I thought it was boring. I have not talked to any kids who have read this book.

So I appeal to you, friends. How do kids react to this book after they’ve read it? I am genuinely curious.

To Joe and Mr. H — I am not persuaded whatsoever by arguments about past Newbery winners. Each year is fresh with no mistakes in it. Saying “the Newbery canon consists of so many titles that many kids can’t relate to at all” only makes me question the choices of past Newbery committees. I can think of several terrible movies that have won Best Picture at the Oscars. That is no argument for giving Best Picture to a terrible movie.

Destinee, I find it alarming that you were on a Newbery committee (last year’s, in fact!) but are “not persuaded by past committees’ decisions”.

Should librarians in 2035 look back on 2016’s decision and question its appeal to children, you wouldn’t care that they questioned the decision *your* committee made? Even though it was the right decision at the time? The year your committee selected a book – that year is unimpeachable! – but past years? They can totally make a mistake and you’re fine with that? Dismissive of it, even? Because what you’ve written is that if modern children can’t relate to books that won even five years ago, you “question the choices of past committees”. That’s really faulty logic in your argument and it makes it seem like each year actually doesn’t matter *after* that year is over. But it does matter because the selections are contributing to a canon of “distinguished” literature.

Your parallel to Best Picture doesn’t stand to the argument, either, because, like the Newbery, it all comes down to personal taste. Does everyone have to love a Best Picture winner? No. So your statement “That is no argument for giving Best Picture to a terrible movie” doesn’t even remotely work because what’s terrible and pedantic to one person (“Birdman”, for me) is delightful and thought-provoking to another person (“Birdman”, for my husband).

I would even argue that your final paragraph is in direct opposition to the first sentence of your first paragraph: “The way I interpret the Newbery criteria, the award should not be given to a book that doesn’t engage its intended audience.” If that were true, then most children would find something interesting and engaging in EVERY medal winner. And we know that isn’t true. At all.

Admittedly, I’ve gushed about WGBT. Does my enthusiasm impart itself on some of my students? Sure. Does it fall on deaf ears with my other Mock Newbery kids? Absolutely. They voted out one of my favorite books in our last elimination rounds. But my Mock Newbery club isn’t for me. It’s for them. And, ultimately, children don’t pick the Newbery Medal. Adults do.

Well, Joe, I’m kind of at a loss because it seems like we’re not on the same page. Here are some points I’m trying to make:

1. No committee’s decision is unimpeachable. As you rightly point out, art is subjective and there are no right or wrong award selections.

2. The opinions of young readers matter to me. That does not mean popularity is the most important factor. It means I have to believe that a book effectively engages children (not *all* children, but some children) in order to get behind it for the Newbery.

I 100% agree with Jonathan’s post below and appreciate very much the questions he asks at the end. I sincerely wish we could be talking about children’s reactions to WGBT instead of questioning the premise that children’s opinions matter.

The first thing to do is the understand that it is impossible for a book to meet the needs of all children. Remember children are defined as 0-14. I think we are so use to “newbery books” meeting the needs of a large portion of 10-12 year olds that we just assume that is for whom a newbery worthy book should be for.

Last year’s committee helped remind us that the award is for any subgroup of children ages 0-14.

It’s easy for us as educators to think about the members of our classrooms or newbery clubs as the intended audience for the newbery winners but there is nothing special about 4th-6th graders that privileged their engagement or interest above any another group of children be they new born infants or high school freshman.

WGBT is a wonderful picturebook for 1st and 2nd graders to listen to as well as a great poetry collection for 4th and 5th graders to read, and be inspired by. Nothing in the newbery criteria says that the child has to be the reader.

Doctor De Soto is a far better read aloud or lap read than independent read but that doesn’t take anything away from this most perfect newbery honor winner because that 1983 committee understood that the book’s intended audience was not a reader but a listener.

The criteria states “Committee members must consider excellence of presentation for a child audience.” Nowhere does it mention the child reader.

I completely agree with you, Eric. By “child reader” I don’t mean “independent reader.” I’m including children who are read to.

Destinee, you said yourself that you thought the book was “boring.” It sounds as if you’ve made up your mind that you don’t think it appeals to kids, any kids, even though you admit it only needs to appeal to some kids. If we were sitting around the table together, I’d kind of feel like I’ve been set up in an impossible argument here. As a supporter of the title, the only things you’ve given me to defend in it are interest-related. You thought it was boring and think kids will think it’s boring. Despite lots of examples on this thread pointing to distinguished poetry writing. And, I think it’s somewhat naive to think NO kids will appreciate this book.

I think it sounds like your mind is made up, but you have my interest piqued. I’m going to read this with my 5th graders and gauge their responses.

Mr. H, I have not made up my mind about this book (except in the sense that I’ve formed my own personal opinion of it based on my taste). I was asking for examples of how kids have reacted to it so I could get a sense of how it works for young readers (and listeners and lookers). The only person who has offered up a child’s reaction is Leonard (thanks, Leonard!).

I’m glad your going to read it to your students. Again, I’m genuinely interested in what kids have to say about it.

So on Friday, I read WHEN GREEN BECOMES TOMATOES to my 5th grade students. Here’s what we did…

I asked the kids to do some freewriting about the seasons. Make a list of descriptive words or feelings that come to mind when thinking about each season. We started with Spring. Then I read the poems in the first Spring portion of the book. I instructed the students to jot down any new words or phrases that the poems stirred up. The room was silent as I read each poem in that first section. They totally soaked them up!

When the Spring poems were done, we talked a little about any connections the kids had while I read and the conversation was awesome. Many kids were relating to feelings or phrases in the poems. Then I had them brainstorm words and phrases that come to their mind when thinking of Summer. Then I read the Summer poems. This time, they couldn’t contain themselves. It wasn’t as quiet, because many were blurting out reactions and feelings as they came up. Again, the conversation was great though.

I read Fall and Winter in the same way and kids quieted down this time naturally, really absorbing the words and poetry. I’ve never read poetry with this group (I don’t most years!) and was really surprised at their reaction. When I read the final poem, the March 20 one again, the class applauded! Then we talked about the seasons again.

Interestingly enough, I’m also reading WOLF HOLLOW aloud to them right now. I really didn’t have any concerns with kid appeal on that one. It is proving to be more challenging than I thought it would be though. They are relating to the characters because of the discussion I am leading with them throughout, but I’m finding that much of Wolk’s language and narrative style is going right over their heads! Making me reconsider it’s excellence in presentation for a child audience. Leonard said that Erdrich is writing MAKOONS to whoever she wants, and the second time around, I am beginning to feel that way about WOLF HOLLOW as well.

WHEN GREEN BECOMES TOMATOES, securely remains in my Top 5 after a read aloud.

Awesome. Thanks for that feedback, Mr. H. I’m really glad your students were into it.

To further add to the complexity, not everyone in a given age bracket will respond to a particular book. I was a fantasy reader as a child, and that’s what a selected for my own pleasure reading. Everything in the Newbery canon that is not high fantasy, therefore, holds no appeal to my child self. I was explaining this to a friend recently, and they asked incredulously, if that included something like BUD, NOT BUDDY. Well, since nothing about the title, cover, or jacket copy of BUD, NOT BUDDY screams high fantasy, it would have fallen to an adult to push that book on me. I think I would have liked it as a kid; it would have appealed to me. It just wouldn’t have changed my life the way that Lloyd Alexendar and Susan Cooper did. As a fifth grade teacher, I turned lots of kids on to the Chronicles of Prydain, but the Dark is Rising Sequence was a much harder sell; it almost always required the audiobook for me to gain a convert. I’m sure some people probably find fantasy books unreadable, but I lived and breathed them as a kid.

I am so glad this blog brought this book to my attention. What a beautiful collection of poetry! I was so impressed with Fogliano’s ability to capture the essence of each season with stunning imagery, unique and perfect word choices, a distinctive, tender style, and most of all a near flawless execution of rhythm and meter throughout – it’s practically music read aloud. Right now, this one is number two on my short list, but I could easily be persuaded in a committee setting. Ghost still has my vote for number one.

While I agree with Destinee that each and every committee must reinvent the criteria anew, that for each committee there is no such thing as precedent, we all know that individually each Newbery book that we read is a new star in the Newbery constellation and when we add stars that push against our individual notions of what a Newbery book really is . . . well, I think, it can inform individual evaluations of books, if not committee discussion.

With 15 people on the committee there is a range of opinions on any given issue or book. Some people will read the Newbery terms and criteria with the idea that more weight should be given to child appeal and others will read them the the idea that less weight should be given. I don’t think that either interpretation is inherently correct; both of them serve as a check and balance system in the Newbery process. Since these opinions have been shaped by years and years of professional and personal experience, it is unlikely that somebody will shed those deeply held beliefs over the course of the long weekend.

Here are some questions I would ask about WHEN GREEN BECOMES TOMATOES if we were specifically discussing child responses to the book. Is there a difference between broad appeal (which is simply another name for popularity) and deep appeal (meaning that a particular book has a profound and/or lasting impact on a reader)? Do some genres inherently have broader appeal than others and does that make them more or less worthy? Does the developmental age of the reader color the child appeal, and if so do we have enough reference points along the spectrum to definitively label something one way or the other?

Jonathan raises an excellent question – Do some genres inherently have broader appeal than others and does that make them more or less worthy? This is really the struggle for me when talking about “kid appeal.” Very rarely do I have kids clamoring for a book of poetry at my library – Shel Silverstein aside. However, when I make it a point to share books of poetry to a group of kids, inevitably they will be clamoring for those particular books after the session. Poetry doesn’t generally have broad appeal with kids. And yes, if I simply handed this book to a second grader to read, it probably wouldn’t be an “appealing” or exciting read. However, if I took this same book, read it out loud to the child, asked her/her questions about particular poems, and fully engaged them in a reading experience, I guarantee that child’s perception of the book would be entirely different and in all likelihood more positive. As adults who are passionate about expanding children’s mind through books, we are looking for the very best books in every genre to share, and by sharing these books, we can create appeal where none existed before.

When my son was 10 years old, I read Dead End in Norvelt to him. Now at 14, he still remembers it as one of his favorite books. He would have never walked into a library and chosen that book to read. It simply wouldn’t have appealed to him. Instead, he would have grabbed a book about dragons, or something funny, or a graphic novel. But because I shared this story with him, he now has an appreciation for the book and expanded idea of what he enjoys as a reader.

The two pillars of the Newbery criteria, literary quality and quality presentation for children, are a bit at odds, aren’t they? I think the examples people are citing as hard sells are “literary”, and it is maybe that very quality that makes them hard sells. Appreciation of Literature-with-a-capital-L is something that has to be learned (from adults) and takes work and encouragement.

It’s interesting how the first pillar, literary quality, gets verbiage in the Criteria about what that includes: style, plot, etc. whereas the only elaboration as to the meaning of “quality presentation for children” is what it isn’t. It is not didactic content or popularity.

The Newbery recognizes literary quality, something that, by and large, children cannot fully recognize or appreciate. But I would like at least some of a Newbery book’s literary excellence to be within the capability of a child’s understanding. Perhaps this would need an assist from a librarian or teacher or parent. Yes, the Newbery is an award “from” adults, so we may have extra responsibility to justify the choice to children: through reading, sharing, and teaching. It would be nice if a Newbery book did some of its own heavy lifting in this regard, but I don’t think that’s quite the same thing as asking a Newbery book be the most appealing book to children.

WHEN GREEN BECOMES TOMATOES is my #1 pick. It may not be my 7-year-old daughter’s favorite book. Left to her own devices, she would prefer to read the Rainbow Magic series. But I read WHEN GREEN BECOMES TOMATOES to her without fear of going over her head or boring her. Weirdly (and I am about to get annoying in a Facebook-y way): the week before WHEN GREEN BECOMES TOMATOES came out, my daughter out of nowhere wrote 4 “seasenol” poems. Here are Spring and Summer (line breaks and spelling corrected by me).

Spring

flowers are growing

winds are blowing

the sun’s coming out

kids are all about

take off your coat

get on the boat

spring is fun

run run run

Summer

I am in the pool

it is cool

but I must follow one rule

don’t run in the sun

although it is fun

don’t run in the sun

I had to check the dates to make sure this was before, not after, WHEN GREEN BECOMES TOMATOES. So *of course* I had to share the book with her. My daughter may not get as much pleasure from WHEN GREEN BECOMES TOMATOES as she does from Rainbow Magic, but Fogliano’s poetic sense is clearly well-aligned with at least one child’s conception of poetry and is attuned to what about the seasons matter to children. That gets “quality of presentation” points from me.

It’s interesting that the Caldecott criteria lump excellence for presentation into the enumerated criteria–

In identifying a “distinguished American picture book for children,” defined as illustration, committee members need to consider:

Excellence of execution in the artistic technique employed;

Excellence of pictorial interpretation of story, theme, or concept;

Appropriateness of style of illustration to the story, theme or concept;

Delineation of plot, theme, characters, setting, mood or information through the pictures;

Excellence of presentation in recognition of a child audience.