Battle of the Books: Compare/ Contrast Two Newbery Contenders

Comparing similar and (not-to-similar titles) is the bones of the Newbery medal. I mean how else are you to determine the best title of the year? You need to see how it stands against everything else (and the criteria of course, always the criteria).

In last Friday’s post, Steven and I compared two popular 2022 fantasy books, OGRESS AND THE ORPHANS and THE LAST MAPMAKER. Today we are taking that exercise a little further by comparing two 2022 Newbery potentials in a game called “Battle of the Books.”

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

- Pick a potential 2023 Newbery contender. It can be one from our nomination list, but doesn’t have to be.

- Look at the Newbery Terms and Criteria and compare the two titles. You don’t have to discuss every category but at least one .

- Explain what one book does better than the other and why that book stands out.

The purpose of this exercise is to see how closely we need to evaluate the books and to look at how they compare against each other. It’s important to remember that all these books are being discussed because they redeeming qualities, now we’re seeing what stands out as the best of the best.

You could choose books in many ways: two books that are the same genre (like our battle of the fantasies), or books with similar themes, or two books that have a lot of nominations, or two books that have only one nomination….

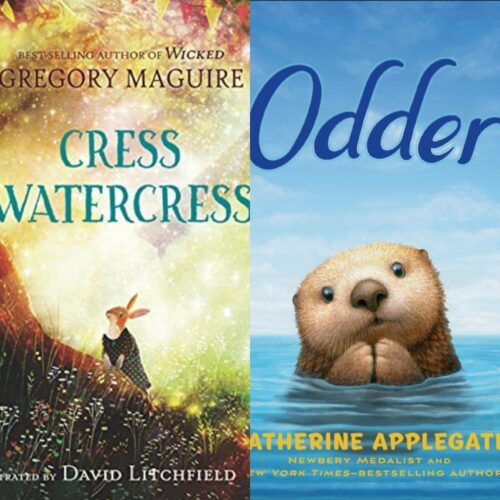

I’ll start with two animal books: ODDER by Katherine Applegate vs. CRESS, WATERCRESS by Gregory Maguire. ODDER excels in characters, with a deep dive into the Otter’s personalities and thoughts while CRESS, WATERCRESS really showcases “unlikeable characters,” in a relatable way. Both have slower plots with deep character development. Overall, I say CRESS, WATERCRESS excels across the board.

Next, two titles with unique perspectives: A ROVER’S STORY by Jasmine Warga (which I thought was nominated but isn’t) vs. The PATRON THIEF OF BREAD by Lindsay Eagar. ROVER gives the reader the perspective of a Mar’s Rover and in BREAD we look through the eyes of a gargoyle. The presentation of ROVER is exceptionally strong with fluid transitions between characters. The dialogue is also phenomenal, particularly how the robots interact with one another. In BREAD, the gargoyle’s perspective is interesting, but I’m not sure if it adds to the story. The language used is decent, but the book particularly excels in development of plot and interpretation of theme, two categories that I think Rover also does well. Based on that I give A ROVER’S STORY the medal.

Please share your own thoughts in the comparison structure. Just look at one comparison per comment, but you can do as many comments as you wish. And comment on the comments of others of course…

Filed under: Book Discussion

About Emily Mroczek-Bayci

Emily Mroczek (Bayci) is a freelance children’s librarian in the Chicago suburbs. She served on the 2019 Newbery committee. You can reach her at emilyrmroczek@gmail.com.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Report: Newberry and Caldecot Awards To Be Determined by A.I.?

Happy April-Fool’s-First-Day-of-Poetry-Month! A Goofy Talk with Tom Angleberger About Dino Poet

Magda, Intergalactic Chef: The Big Tournament | Exclusive Preview

When Book Bans are a Form of Discrimination, What is the Path to Justice?

Fast Five Author Interview: Naomi Milliner

ADVERTISEMENT

Emily-

A Rover’s Story was only published in October so I think a lot of people haven’t seen it yet. It is on my list of potential December nominations.

There have been 3 nominations for A DUET FOR HOME. I would like to put forth a similar but, in my mind, superior book that I will probably nominate for December: MEANT TO BE by Jo Knowles. Both books involve a family in a new “undesirable” place after being forced to leave their previous home. In both books, because of the people she meets there, the protagonist becomes attached to the new place. In both books, the protagonist has a passion (playing viola in DUET, cooking in MEANT TO BE), and there conveniently happens to be a practitioner living nearby. The two Criteria I want to compare here are Interpretation of Theme and Delineation of Character (and really the interaction of the two.) I felt DUET’s generating spirit was a laudable social message that, in the course of becoming a kid’s book, compromised some aspects of literary quality. To illustrate theme, Huey House has to become appreciated by the protagonist to the point of wanting to save it, and so Huey House has to be portrayed as objectively and unquestionably great, filled with great people, and anyone seeing it differently has to be portrayed as ignorant, with bad motives, and a cartoon villain. This affects the delineation of some characters and the implausible development of the plot. MEANT TO BE is, I think clearer-eyed by being character-centered. From there, characters’ interaction with setting naturally illustrated themes such as how circumstantial insecurity feeds personal insecurity and its different manifestations. Ivy loves Applewood Heights and never wants to leave for the simple and very understandable reason that she’s made friends there. But the underlying unhappiness of her parents and others is also completely understandable given the various reasons they are there. Maybe there is no grand message there, but I think the reader, with Ivy, grows up a little more and appreciates more life’s vicissitudes and the whys and hows of people’s response to them.

Thanks for this, Leonard. Looking forward to reading Meant to Be– once my library acquires it!

I know, Emily already had ODDER vs. CRESS WATERCRESS, but I’ll pit ODDER against another book, VIOLET & JOBIE IN THE WILD and look at plot and theme, which are intertwined in both:

In both books, the animals leave one environment for at least one very different one. ODDER is taken from her ocean environment to the aquarium, and we also learn about her earlier stay with the humans. The writing captures the conflict so well: we see it from Odder’s point of view, but also look at it through our own view as human readers. Odder wonders if she should return to the ocean: “Still, Odder allowed him [the human] to take her / back to Highwater again and again. / He was her teacher, ‘ her safe harbor. / The quick-tempered bay didn’t care / if she lived or dived” (171)

In VIOLET & JOBIE, the sibling mice get dropped into the middle of the forest and have to figure out everything. It’s scary, but also invigorating. When they see their second owl from the cover of “the shadowy end of a hollow log,” they experience a mix of fear and awe: “Maybe you have seen Niagara Falls, or stood at the edge of the Grand Canyon. You aren’t going to jump in, but it’s amazing to see. Seeing the big owl was like that.” (138)

Both books do a great job of bringing us into the world of their characters and leading us (but not telling us) to wonder about the conflicts between freedom and danger, and safety vs. adventure. I give VIOLET AND JOBIE a slight edge because I felt a slightly stronger connection with Violet than I did with Odder (oops, now I’m bringing in character…but that’s okay). Also, the ending was surprising and also just right: Violet and her new friend going who knows where, “exploring the world as it was offered to them.” And Jobie passing along memories to his grandkids through storytelling…and then he starts the story we just finished. (227)

Attack of the Black Rectangles by Amy Sarig King and Answers in the Pages by David Levithan both tackle censorship. One book section of a book is being blocked out because a teacher thinks students can not handle what she considers mature content. In Answers in the Pages, a parent tries to take a book out of the curriculum because one line in a book makes it seem like two boys may like each other. In both, the theme is over the top, but in Attack of the Black Rectangles, there is more going on than books being taken away or censored. Mac has to deal with his father, who is emotionally abusive. He also realizes that he likes one of his friends more than a friend. As Mac deals with both of these situations, we see him grow as a character. In Turtles, the characters are all one-dimensional.

The structure of Attack of the Black Rectangles is pretty straightforward, which absolutely works. In Answers, we see a story within a story, but at times, especially in the beginning, it is a little confusing.

I love this game! It’s also a really good way to get yourself to take fresh looks at books that you’ve been working with all year. My favorite science books for kids often feature a distinct narrative voice, usually with some humor, and we have two stellar examples of that this year: HOW TO BUILD A HUMAN vs. BUZZKILL. I’m especially thinking about “Presentation of Information” and “Appropriateness of Style.”

I featured HOW TO BUILD A HUMAN in an earlier post. I appreciated the way the author used humor while at the same time carefully building the reader’s understanding of evolution. She uses a coffee cup analogy to illustrate the slow but steady growth of our ancestors’ brains and relates that to changing climate. Then offers further perspective: “Given this growth spurt, you might think: “Ah we must finally be brainier than dolphins!’ Nope. If alien scientists and visited Earth a million years ago and calculated the brain-to-body ratio of hominins versus dolphins, dolphins would still have had the advantage. But we were catching up.” (37)

Brenda Maloney also has great fun sharing insect information in BUZZKILL. Her chatty, lighthearted voice is maybe even more pronounced than Turner. Here’s part of what she writes about the huge number of insect species: “Scientists have only been able to come up with rough estimates of the total number of insect species on earth. They put that best guess somewhere between 3 million and 100 million species. What does that mean in terms of the actual number of insects? It’s like a crap-ton. Obviously, ‘crap-ton’ is not an objective number. I merely say that so you will know there are a lot.”(4) She had me at crap-ton. Then the following pages go on to introduce the diversity of insect life with specific examples, grouped logically by body parts and functions, and filled with fascinating information. And that’s all before she gets to the benefits from and threats to insects. The big question about this one is “children as a potential audience.” At 366 pages, mostly unillustrated, this just doesn’t look like a typical kids’ science book, even for the older 12-14 part of the Newbery age range.

It’s actually because of its unusual presentation that I’m giving BUZZKILL the edge, at least for now. The Newbery Criteria also mention “individually distinct” it the definitions part, and I feel like this book is unique in its attempt to share a crap-ton of information with a unique presentation that trusts in the richness of her topic, the engaging voice, and the abilities of older kids to read and learn at this level, in this format.

I am still waiting for my hold on ROVER to come in, but I agree with Emily that the gargoyle from BREAD didn’t add enough to the story to justify the word count he’s given. I wonder how many other readers skimmed quickly through the middle gargoyle chapters to get back to Duck’s story (though the opening and closing gargoyle chapters were great in my opinion).

There’s one detail from BREAD that really bothered me. Why would a street gang of pickpockets and thieves wear something as recognizable as a red glove on one hand? Are they trying to get caught? The Red Swords are supposed to be menacing, but I was reminded of the Wet Bandits from Home Alone who think it’s cool to have a calling card so all their crimes can be attributed to them.

I’m also going to do ATTACK OF THE BLACK RECTANGLES, which made the early six. I mentioned elsewhere wanting people to look at PLAYING THROUGH THE TURNAROUND by Mylisa Larsen with the RECTANGLE comparison in mind. Both feature student activism, though in TURNAROUND, it’s against the cutting of extracurriculars instead of censorship. Both feature other subplots such as crushes and parent issues. I’m basically going to say the same thing as I said about DUET FOR HOME vs MEANT TO BE. I feel like RECTANGLE starts with the theme as its guiding spirit, and in order to make the message as unambiguous as possible, I felt character suffered. As a student activist, Mac feels fully-formed from the start and doesn’t really develop on that front. He is just the solution to the problem. His big character growth is with respect to an unrelated (and more interesting) conflict with his father. But that gets resolved fairly early on (and really begs for comparison with AVIVA.) TURNAROUND starts with characters, and the kids grow into activism (and grow in other ways). In fact, as the person who recommended the book to me pointed out, there is no inkling at the beginning of the book about what it will become. One would guess from the beginning it’s a standard beloved-teacher-helping-kids-find-themselves book. I love that even after their big statement, the kids are changed but not complete. They are still on a path. Another teacher points out later that while their spirit was admirable, there are real avenues to pursue if they are serious about change: “‘We have an election coming up in two weeks. Students will not be allowed to vote, but parents will. And not all the candidates agree with the current board’s philosophy. In fact there are quite a few running this time who do not.’ ‘Which ones?’ Quag asks. He realizes this is the first question he’s asked a teacher in years, and he gives Harken a scowl” (241). And that ties in nicely with what some of the characters are going through with parents, whereas as mentioned above, the parent subplots feel separate in RECTANGLES.

I want to compare the delineation of setting in ANYBODY HERE SEEN FRENCHIE by Leslie Connor vs THOSE KIDS FROM FAWN CREEK by Erin Entrada Kelly. In FRENCHIE, the descriptions of the Maine countryside and the outdoor survival scenes give the book a strong sense of place. In FAWN CREEK, the portrayal of setting exudes the heat and humidity of the Louisiana environment. The settings are also enhanced by the differences of the people in the communities. In FRENCHIE, the individualism of the residents distinctly represents the location. In FAWN CREEK, the social structure is stratified even though the story takes place in a small town. Both settings are well delineated but my vote goes to FRENCHIE for capturing a unique locality.

YAYYYYYY FRENCHIE!!!