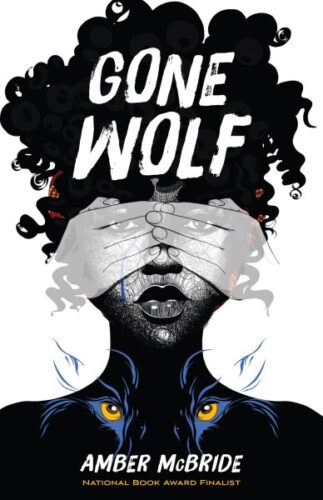

Heavy Medal Mock Newbery Finalist: GONE WOLF by Amber McBride

Introduction by Heavy Medal Award Committee Member Aryssa Damron:

“We all have to look in the mirror and decide what we believe in.”

In this inventive, daring middle grade debut by National Book Award Finalist Amber McBride, history transcends the boundaries of time as a young girl living in pandemic-era Charlottesville grapples with intergenerational trauma through her imagination. Black History, science fiction, grief, and family intertwine in this upper middle grade novel that is cleaved in two like the life of our protagonist, Imogen. It’s through Imogen that we experience both worlds of the novel.

The first half of the novel, subtitled BLUE, takes place a hundred years into the future, in the Bible Boot. We begin in a cage, as Inmate Eleven is being given the infamous doll test. As Inmate Eleven learns what is to be of her life in the Bible Boot, where Blues are kept enslaved and used for labor and organs for “Clones,” she decides it is important to name herself. Of course, her wolf, Ira, has always had a name. Ira has been her constant companion for as long as she can remember, but she can tell that Ira wants to truly go wolf–to escape to somewhere beyond their wildest imaginations.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

In the second half of the novel, subtitled BLACK, we meet Imogen, a 12-year-old girl living in pandemic era Charlottesville. The year is 2022, and Imogen is not okay. We meet her and her therapist simultaneously, the newest medical professional brought in to help Imogen work through what she has experienced as an immunocompromised Black kid impacted by the past few years and generations of trauma beforehand. As Imogen tells the story of Inmate Eleven, we see her unpacking the way that trauma is manifesting in her body.

This book is very fast-paced, and the short chapter length helps the reader fly through the book, constantly turning pages to see what will happen next. As the book turns from Blue to Black, though, the pacing slows a bit, which feels like a perfect match to what that reveal allows the reader to do: to leave the life and death situation of Inmate Eleven in the Bible Boot and slip into the anxiety-ridden mind of Imogen in Charlottesville.

The themes of grief, trauma, and Black History are integrally woven throughout the novel. Even in the dystopian first half of the novel, where Inmate Eleven is literally blue-skinned because she is consumed by sadness, there are elements of the fake history woven into her chapters.

The setting is an integral part of this story, especially in the first half. McBride realizes this horrible future with such exacting detail, giving shape to a horror story for Inmate Eleven and those who do not learn from their mistakes.

Characterization is where this novel soars—Imogen, in her second half, could very easily just read as a modern day Inmate Eleven, but through McBride’s careful delineation of Imogen’s mental health and relationships, instead her trauma and experiences allows the reader to reflect on Inmate Eleven and what is imagined versus lived.

Thought-provoking and gripping, GONE WOLF is certainly a contender this year. Fans of McBride’s YA work will certainly enjoy this middle grade debut, and middle grade readers looking for the grit and history that often leans towards older readers will find a lot to chew on in this prose novel.

Heavy Medal Award Committee members and others are now invited to discuss this book further in the Comments section below. Let the Mock Newbery discussion begin!

Filed under: Book Discussion, Heavy Medal Mock

About Emily Mroczek-Bayci

Emily Mroczek (Bayci) is a freelance children’s librarian in the Chicago suburbs. She served on the 2019 Newbery committee. You can reach her at emilyrmroczek@gmail.com.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Name That LEGO Book Cover! (#53)

Cover Reveal and Q&A: The One and Only Googoosh with Azadeh Westergaard

Exclusive: Vol. 2 of The Weirn Books Is Coming in October | News

Fighting Public School Book Bans with the Civil Rights Act

North Texas Teen Book Festival 2024 Recap

ADVERTISEMENT

This was the last finalist I read, and I’ve been thinking about it a lot in the few days since – I apologize if this runs long.

This is basically two books in one. The second is a powerful, timely story about a girl working through the trauma of losing family from Covid and the trauma of racial violence in events like the Charlottesville march.

The first is a dystopian sci fi story set in the 22nd century in the aftermath of a second Civil War. I came to the book knowing nothing about it, so I took this section at face value, and as it went on, I became more and more worried about its quality. The characters are flat, the political commentary is blatantly on the nose. The flash cards at the end of each chapter make less and less sense as the book goes on. (Why would there be ones that say things like “you might hear about protest/escape/‘good trouble’, but those things are bad”? They just wouldn’t tell inmates about those concepts.)

Imogen is understandably naive, but also incredibly wise and virtuous about things she’s just learned, to the point where it felt like she was an archetypal Mary Sue. That turned out to be more correct than I could have thought. The last quarter of the section goes off the rails, plot-wise – in about fifty pages, the idea of escape is raised, it happens with minimal resistance, they get picked up by MLK, experience two separate instances of 1950s-style racial violence, and Larkin collapses at an MLK speech.

And then it ends. The twist is that this first section is a story that the protagonist of the second section has written to cope with her experiences. Like I said, I didn’t know this going into the book, so I was genuinely surprised. Looking at reviews, GONE WOLF was very well received, which probably means people either a) thought the first section stood on its own or b) thought the second section added a layer to make the first section better (or ideally, both a and b). I’ve already given my thoughts on the former, but I don’t think the latter holds for me either.

There are links from the second section to the first section, but some were there regardless. The disease/vaccine were already obvious references to Covid, and President Tuba couldn’t have been anyone except Trump. (I had the thought that “Tuba” was a name a kid would come up with to make fun of Trump, and was right.) If you know your civil rights history, more of the links were already there, and maybe made things confusing. I understood “Till” to be Emmett Till, and when he was explained to be a kid who was killed by Elitists, I assumed this was the language they had available to describe a 20th century lynching, even though the Elitists came about in the second Civil War. But then we meet MLK and Rabbi Heschel, and it’s explained that they’re not the original ones, they’re just named after them. But that made me think – was there actually a second Till who was also killed in racial violence? What is the implication there?

The answer, I guess, is “who knows, a kid wrote it.” How are the Elitists living to 150+ years old? No amount of organ transplants/blood transfusions would get you there, but the science doesn’t have to work, because again, it’s a kid writing it. I thought while reading that the political commentary would be stronger if Tuba wasn’t so obviously Trump – what if Trump loses in 2024? Is the message of the book that we dodged a bullet, and not that racism exists separate from him and we still need to be vigilant about the rise of fascism? Will this book hold up in 20 years when Trump is gone? It turned out I was thinking too deeply about it, because this was all just the news filtered through Imogen.

I guess that’s my big problem with the twist. It’s conceptually interesting, the idea of Imogen writing a story based on her experiences, but we’re asked to spend a few hours actually reading it, so it needs to stand on its own. Like I said, plenty of people seem to think it does, so this is obviously a matter of opinion. But the twist for me was like being told “it was all a dream,” which is frustrating. Even moreso since the second part does stand on its own, and it even sometimes quotes from the first part in small bits to get its point across – that could have been the full strategy, just excerpting relevant parts where needed.

If ALEBRIJES had an additional section where it was revealed that Leandro was actually living in the present day and wrote the book metaphorically about contemporary racism towards Hispanic people, that might have worked, although it would probably be a hat on a hat – Alebrijes works as a story on its own and that theme is already there. I just wish the first half of Gone Wolf worked by itself, too.

Brian brings up some excellent questions about GONE WOLF. Those two separate, very different stories and the ways they relate to each other are really key to the reader’s experience. Brian articulates it very well: “people either a) thought the first section stood on its own or b) thought the second section added a layer to make the first section better (or ideally, both a and b).” I would adjust that a bit though, because I think “b” is really the only way the book succeeds. “A” has to work to some degree, but I don’t feel it has to hold together as strongly as a full-blown novel (like ALEBRIJES) for this book as a whole to work.

For me, the first part was instantly engaging, but as it got further I did wonder if it was holding together; Brian provides some good examples of those moments. I started to think: “okay, maybe not a Newbery contender after all,” assuming it would be just this one thread.

But the twist in the second part did work for me. It made me take a completely different look at what the first half meant, and that worked. I feel like we need to be holding those two stories in our mind, the imagined Blue in 2111 and the “real” (but still not our exact reality) Black in 2022, for the whole thing to come together. It’s challenging, not without flaws in its execution. And not for every reader. I’m eager to hear how Heavy Medal readers respond to this one, and especially how we think this book will connect with kids (or not).

Like both Brian and Steven, I was well engaged with the first half of the book, but as I read on in the ‘Blue’ section when she met MLK and went to a rally, it was getting a bit much for me. But, like Steven the twist in the second part of the book worked well for me, and I too looked at the first part of the book in a whole new light. I thought the author did an exceptional job of putting a face to the reality of racial trauma and generational trauma (explained on p. 320) on the mental health of children in ways I am still thinking about. When that is combined with the isolation of the pandemic and the losses Imogen had in her life, it helped me to understand the complexities of Imogen’s mental state. I was happy she had a therapist and a ‘Big Sister’ relationship that saw those complexities. This book shines in delineation of a character and Interpretation of Theme, and I found the plot idea cutting-edge.

Aryssa Damron’s introduction to this book is excellent!

Steven and Brian, great notes on every book! Your thoughtful perspectives have me flipping back to the book for a re-read and deeper dive. Is that what it is like on the Newbery? I hope so.

I completely mirror Steven’s breakdown of the two-story narratives. The first half of the book hooked me. I liked the dystopian, science fiction worldbuilding (is this one word, two words, or hyphenated?) The story of “Inmate Eleven” moved fast, and I could only put it down once we reached the modern-day tale of Imogen.

The second half of the book felt different. The setting and themes were great; I liked the COVID-19 tie and idea of building a new community or “pack,” but Imogen’s characterization moved slowly in the modern setting in a book that began with dystopian action. But really, the global pandemic is a time when the fast-moving world stopped, and the second half was a time of personal survival. That could be a part of the story’s organizational choice.

I was introduced to the genre of Afro-Futurist fantasy as a pre-reader for Random House in 2022. I read NUBIA and interviewed author Omar Epps. He explained the genre’s premise, combining technology, history, and relationships from the perspective of characters of African descent. Over the past several years, I have enjoyed the critical way these books address systems of slavery, colonialism, and racism for young readers. Most recently, I spent three months deeply analyzing Tomi Adeyemi’s Children of Blood and Bone (Book 1.)

I brought this experience to my reading of GONE WOLF. Amber’s prose was full of emotion and was moving. She expertly addressed the feelings of grief, fear, and hope from a unique and vital perspective. Gone Wolf could have been 100% dystopian and would have been great. I appreciated that she went further and am glad it is a part of the discussion.

Oh boy! Thanks, Brian, for the helpful breakdown of potential reactions to this book. I am definitely in the “B” camp and thought that the second section made the first better. As I was reading the first half I thought that the themes were communicated very clearly, but the metaphors were way too on the nose and lacked elegance (e.g. the Bible Boot, Clones trying not to say the word “white,” The Fugitive Blue Act, etc). But then when I got to the second half, that stylistic choice made TOTAL sense. The introspection and “Black History for Kids” sections of the second half were a beautifully orchestrated counterpoint to the rushed plot and the hasty “Bible Boot Learning Flash Cards” of the first half. I just wonder if the unclear organization would cost this book the Newbery, because I DO think the premise of the book is not made clear for readers until about two-thirds of the way through the book. But I suppose that was the entire point of the first half, to force readers to experience this cognitive dissonance that is a result of centuries of injustice and generational trauma. So on the one hand, this book doesn’t meet the Newbery criteria for clarity — but on the other hand, I don’t think this book would have been as great if it had been written any other way. (If reading my comment feels like being on a seesaw, it’s because my brain has been on the GONE WOLF seesaw for days!). So much to say about the structure alone and that’s not even going into the themes and character delineation! Definitely top 5 for me, would love to discuss it further.

I went into the book expecting time shift every other chapter like some books do and spent most of the book just waiting for the second part. Granted, I enjoyed the plot of the first part. After the first part ended, I was then thinking to myself, ok, where is this going? I think I felt like the book would only make sense at the end, and it still didn’t. I know it would not have been the same book without the second part, but I hoped it would just be the first part honestly. I should probably read it again knowing what the second part is like.

I think the first part was fully fleshed out, and I just didn’t get that from the second part.

I had a broadly similar experience to others here, but I could be persuaded that this merits Newbery consideration.

AN AMERICAN STORY asks a question on how to teach a difficult topic, and in the author’s note, Alexander expresses the hope his book will prove useful. GONE WOLF’s dystopia seems like an answer to this same question. Even the unsubtle flash cards and textbook excerpts have real value to the child reader in this respect. If you compare the two directly in terms of the Criteria: presentation of information, appropriateness of style, interpretation of theme/concept, GONE WOLF might win.

I think it’s still worth directly comparing the first half of GONE WOLF to a comparable stretch of ALEBRIJES (maybe through the strawberry theft) on technical merits as science fiction. They really are doing very similar things up to that point. On those grounds (without considering larger structural questions) I personally preferred GONE WOLF in all the Criteria (the three aforementioned plus character, setting, and plot). And even in larger structure, I found ALEBRIJES rather conventional. It might’ve been more distinctive adopting a GONE WOLF-ish tactic. After all, ALEBRIJES is framed as an as-told-to-me-by-Leandro story, so it might’ve been cool if the epilogue were inserted in the middle and expanded, like GONE WOLF with flipped times periods (or THE LOST YEAR even.)

Given that DREAMATICS and LOST LIBRARY aren’t on our discussion list, I think one could compare the second half of GONE WOLF to SIMON in their handling of trauma. Like DREAMATICS and LOST LIBRARY, GONE WOLF finds a natural home for its imaginative elements as part of coping whereas I’m still unconvinced the wacky and improbable elements in SIMON are convincing as simply in the “real” world.

I am not sure about GONE WOLF in toto, but I respect that it did its thing. And where I can directly compare it to other contenders, it’s not clear to me it’s less successful.

Not much new to add to the discussion since I agree with so many of the points people already made. I did see similarities between Gone Wolf and The Probability of Everything in that the protagonists of both stories create elaborate stories to cope with the grief of a lost loved one and most readers seem caught off guard by the big reveal, It’s interesting that Probability isn’t on people’s radars for Newbery.

The main issue I had with Gone Wolf is the lack of difference in writing style between the first and second halves. I understand the simplistic thinking and communication of Imogen in the first section because the character hasn’t been formally educated, interacted with the outside world, etc. I expected the writing in the modern-day section to be more polished or evolved since Imogen is clearly a very cerebral 12-year old, but the language felt exactly the same. Because of this the book falls short for me in the “appropriateness of style” category.

GONE WOLF also reminded me of THE PROBABILITY OF EVERYTHING! Unfortunately, the latter isn’t eligible for the Newbery because the author is Canadian. If we could compare the two, I’d say PROBABILITY is superior in every way.

Brian and Steven helpfully gave us a lens through which to think about Amber McBride’s stunning GONE WOLF. I agree with Steven that “we need to be holding those two stories in our mind, the imagined Blue in 2111 and the ‘real’ (but still not our exact reality) Black in 2022, for the whole thing to come together.” But for me, come together it does.

McBride excels at delineation of characters and setting, development of plot, and interpretation of a theme. The captor/captive relationship between “the lady in blue” and Inmate Eleven/Imogen is established at the outset, as is the cold, concrete living quarters Inmate Eleven/Imogen shares with her only friend, Ira, a genetically modified dog. The Bible Boot Learning Flashcards that follow each chapter enhance the characters’ descriptions of the Bible Boot and the pretenses under which Inmate Eleven/Imogen lives in its capital. The pace of the novel’s first half—particularly from the time Inmate Eleven/Imogen is presented to President Tuba as the best biological match for his son, Larkin—feels fast when compared to Inmate Eleven/Imogen’s slow eating, thinking, and speaking.

While the novel’s first half can’t be mistaken for anything other than a post-Trump era dystopia, without this setting, the fear and panic of living in novel’s second half, set early in the COVID-19 pandemic and at the height of Black Lives Matter movement, would not feel so real. Or does the second half better inform the first? Does it matter?

In the novel’s first half, Inmate Eleven chooses a name for herself because she is alive and “real the way people in books are real.” (12) In the second half, Imogen learns the names of Civil Rights movement leaders, lists “Important Names to Me” (292) and reads #sayhername #BLM over and over again in excerpts from Black History for Kids, the book her therapist gives her. The pace of the novel’s second half aptly feels slow, like it did while living through the pandemic.

One additional comment about the writing is the perfect use of repetition. FIGHT CLUB author Chuck Palahniuk and Kate DiCamillo both excel at this. Not too often to be annoying, and just far enough apart that the reader forgets to expect it, and then we get an observant analogy with the phrase, “I know X doesn’t LOOK like Y but it FEELS like it.” McBride shows us Imogen’s unique perspective through these analogies. Sensory successes. In MONA LISA, Ray mostly tells us about what da Vinci saw by describing his notebook entries. The message about observation is effective in both, but GONE WOLF’s writing is poetic in those moments.

I am really very conflicted about GONE WOLF. I really enjoyed the first half (and this is saying something as I’m not often a fan of dystopian or sci-fi) and I really enjoyed the second half, but I don’t feel like I enjoyed how they came together. The connections did not feel strong enough to make it feel as if this was one continuous story about one child, instead of two totally separate stories. I could feel Eleven/Imogen’s sadness, fear, and confusion throughout and her characterization was definitely a high point for me.